The last couple weeks of Sub-I have gone much more smoothly than the first few. Although that first sink or swim call definitely contributed to that-if you can learn to admit and manage 5 patients in one day, then an occasional admit every other day doesnt have quite the same terror inducing power.

And I realized I have neglected to tell you any patient stories from SubI…now this is again because of the aforementioned busyness and studying, not because I havent had any interesting patients. Here are a few brief summaries of the folks I have had the *dubious* pleasure of treating during the last month

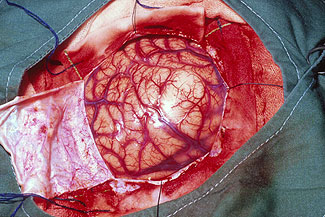

1)A 50 yr old man who was brought to the paramedics following a grand mal seizure. He had a history of seizures 10 years previous for which he took dilantin, but had since become noncompliant with meds. His history was additionally signficant for Crohns disease and a blood clot in the brain necessitating a right craniotomy. What is a craniotomy?

That’s right, it’s zombie bait surgery…your skull is cut open and the most delicious parts of the brain (or the one causing the problem, whatever) are removed. As you can imagine, this can occasionally lead to an indented sort of look for the patient. Luckily (or not) for our patient, he had no knowledge his sull looked caved in, or even that he had undergone a craniotomy, as the piece of brain removed from him had something to do with his short term memory, as per the family’s description. Oh and btw, he was postictal (the state of confusion following a seizure) and wandering naked about the ER when I first went down to attempt an interview him.

We loaded him with dilantin, an anti-seizure medication for while he was in the hospital, but he refused to take it saying he hadnt had a seizure in 10 years and didnt need it, nevermind the one he was brought in for. Until, that is, his mother came him and told him he was taking it because her and the doctor said so. To which he immediately agreed. I guess no one ever gets over being scared of their parents

Assesment/Plan: EEG negative for current seizure activity, MRI declined, pt sent home with dilantin and a stern lecture from his mother.

2) A 56 year old cocaine abuser in for chest pain radiating to the shoulder. That’s right its everyones favorite rule out ACS (acute coronary syndrome). His history was significant for hypertension and heart failure, not to mention the cocaine abuse which can precipitate heart attacks through vasospasms. His social history revealed that patient abused cocaine while his girlfriend used heroin. How long do you suppose they’ve been together? 17 years. Wow perhaps the marriage counselors are missing a key therapy here.

Assesment/Plan: Three sets of cardiac enzymes negative, no EKG changes, a beta blocker to decrease afterload on the heart and a negative stress test showed our gentleman was not in fact having a heart attack, just the standard cocaine buzz. Discharged home with the admonition that coke is for drinking not snorting. Wonder how long til we see the girlfriend

3) a 29 year old mixed martial arts fighter with multiple MRSA abcesses including a rectal one. While his choice of career could lead to abscess potential, the sheer number and the fact that they were all colonized with MRSA (a drug resistant bacteria usually only accquired in the hospital) he was a rather interesting case whose etiology we never quite figured out. But the real kicker is that I am a pretty big fan of UFC and all those fighting leagues…so while this fine fellow was not technically one of MY patient, but rather on my team, I would just pop in and chat over his fight record and techniques with him. He’s still a small time fighter and not one I have followed, but it was still the closest I have come to meeting a sports star I actually gave half a damn about.

Assessment/Plan: You really think I am going to tell a man who beats people up for a living to do anything? We pumped him full of antibiotics and set him loose on particularly difficult staff members

Of course there were a whole grab-bag of other ill folks, with seizures, diabetes, abuse, and the usual hospital culprits, but like any good med student I know that both audiences and attendings tend to stop listening after the 3rd patient, so I will leave you with that thought.

Recent Comments